By Laurier Mandin

Ever heard of Hydrox cookies?

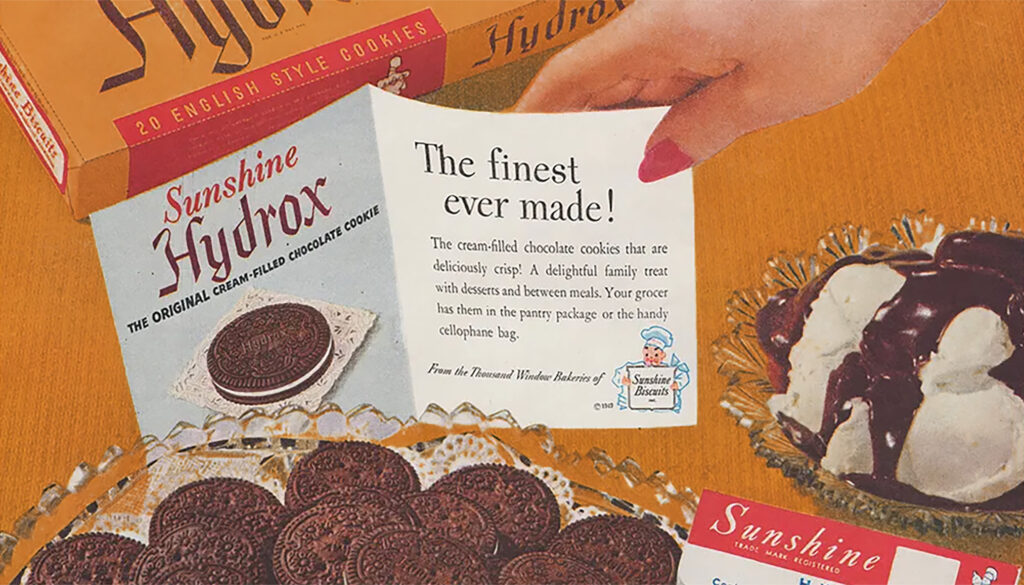

Hydrox was the original chocolate sandwich cookie with a creamy vanilla centre. It was introduced by Sunshine Biscuits in 1908—and imitated by Nabisco in 1912.

Hydrox cookies were possibly superior to Oreos, with crunchier chocolate wafers that didn’t become soggy when dipped in milk. They were also kosher, while the original Oreos were filled with creamy, deliciously sweetened pig lard.

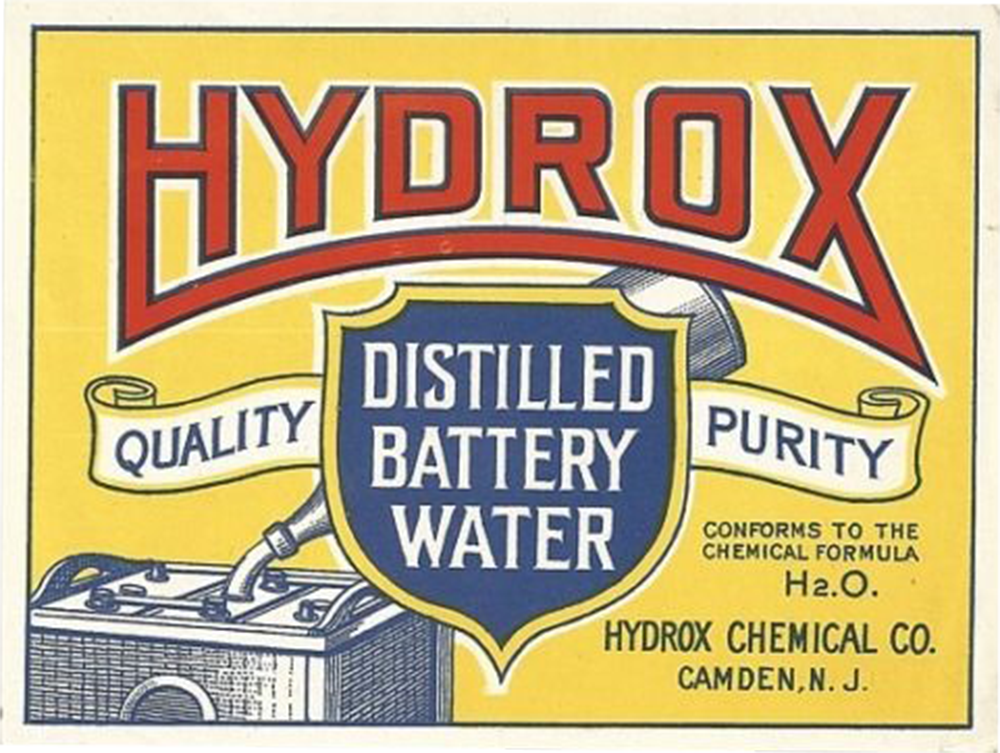

Sadly, the Hydrox name, a mashup of “hydrogen” and “oxygen” that was intended to sound natural, shared its trademark with the Hydrox Chemical Company. Even without that confusion, the name never sounded remotely appetizing, let alone playful or smart.

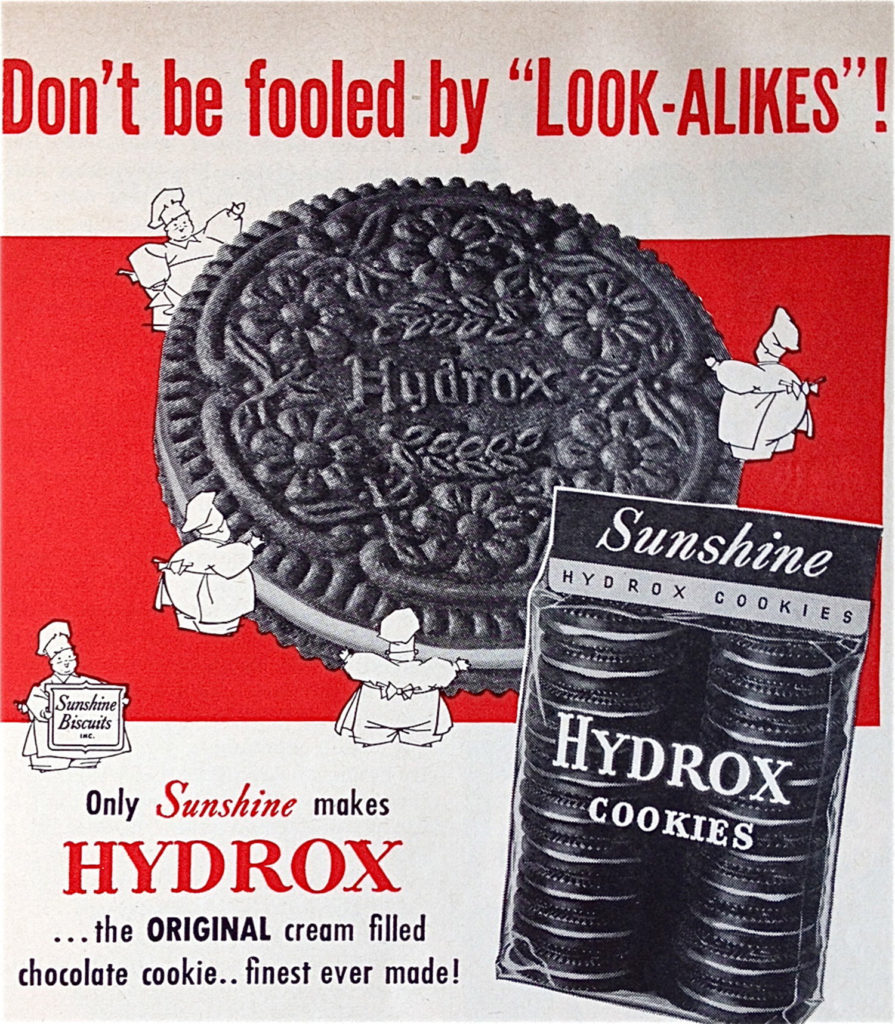

With better branding (including an alluring brand name sandwiching the “re” from “cream” between an O on each side), the copycat Oreo quickly stole the market. And although Hydrox cookies continued to be sold for nearly a century, Sunshine was never able to convince consumers it was the “Original and Finest.” Hydrox fell short—and ultimately lost billions.

Marketing history is packed with stories of copycat brands that overtook the original. Lego is a shameless copy of Kiddicraft building bricks, whose patents fell short of covering Scandinavia. Hershey’s Kisses, the Big Mac and Barbie are knockoffs of products that preceded each by more than a decade.

That’s why the greatest fear of nearly every inventor is being imitated. Flattering though it is, every copycat brand’s main goal is to play on the orginal’s weaknesses—and crush it like a Hydrox.

On a recent “Product: Knowledge” podcast (E5: Crossing the Chasm), we discussed the importance of developing a Minimum Viable Product (MVP). But we also talked about taking innovative concepts to a strategic beachhead with what is known as a “Whole Product” to create early success.

By definition, an MVP is the leanest, simplest version of the product that can exist and perform the customer job for which it is intended. Generally an MVP is targeted to early customers, with the intent to test the product’s desirability and effectiveness, while drawing feedback to inform feature selection and development. Or, according to D46731, who coined the term in 2001:

The MVP is the right-sized product for your company and your customer. It is big enough to cause adoption, satisfaction and sales, but not so big as to be bloated and risky. Technically, it is the product with maximum ROI divided by risk. The MVP is determined by revenue-weighting major features across your most relevant customers, not aggregating all requests for all features from all customers.

In short, an MVP is a real-world test. Its job is to determine if there is a market for your product without risking more resources than necessary. To succeed, it must also be a Whole Product.

Wait, what?

A Whole Product, as popularized by Geoffrey Moore in his marketing classic “Crossing the Chasm” is a standalone product that serves 100% of its intended function for the end-user, in a way that creates compelling value. In order to achieve its main job, it does not require third party training, plug-ins, accessories or other additional purchases.

A Whole Product should also come complete with everything the customer needs to experience success in using it. That means it should include solid support, documentation and warranty—as well as appealing and appropriate branding.

But you know what? Consumers have come to demand all of these things. Being minimally functional, much less “whole” is insufficient to breed obsessive fans.

That’s why there is something more important than a Whole Product or an MVP to enter a marketplace.

It is your Minimum WOW Product™ (MWP).

A Minimum WOW Product is not bloated or excessive. It’s simply one that provides a better-than-expected experience at every single touch point.

A Minimum WOW Product is so well-designed and supported that it organically generates five star reviews. Everything from the marketing, packaging and sales presentation to unboxing and customer service tie together in achieving a succession of above-and-beyond experiences.

But how does that discourage competition and copycats?

Think about it: the first two things a prospective competitor looks for in an existing product are validation of market demand and shortcomings. So one of the biggest mistakes an innovative product can make is to demonstrate the concept is attractive and viable, yet fall short of delighting buyers. If your products validates a need in the market, yet leaves customers hungry for something better, it’s like blood in the water to well-financed sharks.

One of the biggest mistakes an innovative product can make is to demonstrate the concept is attractive and viable, yet fall short of delighting buyers.

Unlike an MVP (which can be functionally complete but have other weaknesses), or even a Whole Product, which blunts competition by leaving no clear gaps for a competitor to jump in and fill, a Minimum WOW Product creates an unbeatable precedent. Copycats are discouraged early on, seeing they have a nearly impossible road to hoe in displacing a market leader with legions of obsessed advocates. (Just ask Pepsi.)

Think how the powerhouse Nabisco Foods saw weakness in the original chocolate-and-vanilla sandwich cookies. Hydrox was an innovative and desirable concept but had a simply gross name. With an arguably inferior product, Nabisco’s Oreo went on to become not only the category winner, but the most popular cookies on earth.

Hydrox cookies were more than an MVP, and were fundamentally complete. The cookies were novel, attractive, kosher and delicious, but had one fatal weakness right across the front of each package. Hydrox missed an essential part of WOW.

Can your MVP be an MWP?

Absolutely, unless it is purely a test and is restricted to a Minimum Viable Audience, in the clear context that it is a beta or pilot version. Still, make sure it’s a Whole Product, support the heck out of it, and apply your learnings sensibly and speedily. Hunt down weaknesses ruthlessly and fix them. At this point, it’s time to make improvements that become harder with scale, and to put your “WOW” moments in all the right places—usually core functionality, customer experience and support.

When it’s time for serious market entry, attack your first beachhead with your Minimum WOW Product. The WOWs should come from every touch point, from the website, branding, packaging and unboxing through the its full lifecycle (ideally when the customer graduates to your next product).

A Minimum WOW Product is not perfect, or finished evolving. It is simply one that is innovative, complete, exceptionally well supported, and delivers an amazing overall experience.

It’s how you create an Obsession Brand™ that grows to own the market—and defies even the behemoths to challenge it.